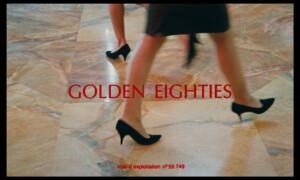

With Corina Copp, Tobi Haslett, Courtney Stephens, and Lynne Tillman + Family Business, Chantal Akerman, 1984, digital projection, 17 mins

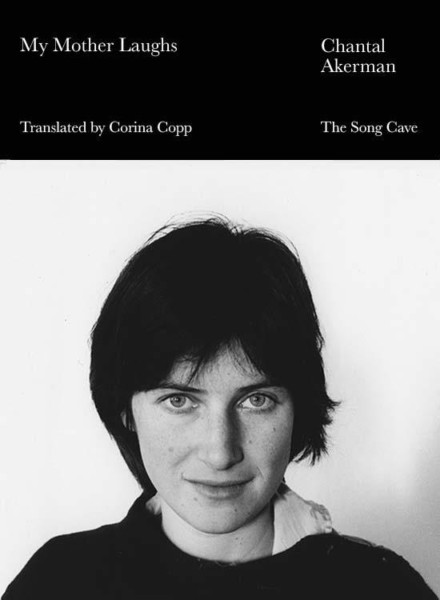

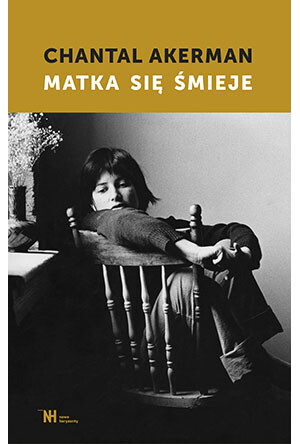

In a review of Maniac Shadows, Chantal Akerman’s installation at The Kitchen in May of 2013, critic Amy Taubin pointed out the filmmaker’s use of the phrase “old child” as self-descriptor in the opening chapter of My Mother Laughs (Ma mère rit), a short memoir Chantal had recently published with Mercure de France, in Paris. This old child, Taubin writes, is she who has “defined herself by repeatedly running away from her mother’s house and returning to it from all the far-flung places where she made the great work referenced in the installation — as if those works were elaborations on the child’s game of ‘fort-da.’”

This old child, Chantal writes in the book — published this month in English by The Song Cave, a small art, poetry, and translation press — “was born an old child and as a result, the child never grew up. It moved in the world of adults like an old child, and didn’t manage very well. The old child said if its mother passed away, it would have nowhere to come back to.” Back and forth: a tending. We tend to. We attend to. She tended to here and elsewhere. To herself, and to her mother. To her depression, to her delight.

In the translator’s note to My Mother Laughs, I try to extend the back and forth. The old child, I write, is she who is “simultaneously naive, accomplished, and self-aware—ongoing. An adolescent tense, possibly. An artist’s tense, a nomadic tense.” She was, and is, ongoing. Yes, she often asked where she would be without her mother; and she centered Nelly Akerman in her work from films like News from Home (1976) to No Home Movie (2015). But her writing was what saved, what harnessed her humor, her delight. She wrote about calling her friends from the payphone in the street, that delight. I write in a piece about Family Business (1984), in which the filmmaker plays herself as a Belgian daughter on a hunt to find her rich uncle in Los Angeles: “It is the telephone, I’d like to imagine, that sutures the voice to comedy, that brings daytime into night, as Akerman does not tend to use it as other directors, say to charge a scene with meaning or suspense. Instead, it is a place to make up one’s story.”Actress and comedian Colleen Camp, perhaps best known for playing the maid Yvette in the 1985 movie Clue, or for her appearances in the Police Academy movies, co-stars in Family Business, as does Aurore Clément, she of Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978). Anna, a known version of Chantal Anne Akerman, was an embodiment of the back-and-forth as she takes trains, moves from hotel room to mom’s bed to her own apartment, lets the voices of others play.

In my favorite moment in Family Business, Chantal cocks her head to one side to eavesdrop on Camp as she talks to her lover. “Tell me that you love me,” Camp says into the phone. “Tell me that you love me.” As Taubin put it: “She is not speaking to us, but she allows us to overhear her words.” It was true formally, such as in this scene, and it’s true in this book. I translated it, and read it now, as if allowed to overhear. I’m forever grateful for that allowance.

Corina Copp

Copies of My Mother Laughs will be for sale at the event.

Tickets – Pay-what-you-wish, available at door.

Please note: seating is limited. First-come, first-served. Box office opens at 6:30pm.

Light Industry is a W.A.G.E. Certified organization, supported, in part, by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts as well as public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.