The TIFF Cinematheque retrospective News from Home: The Films of Chantal Akerman begins Friday, November 1.

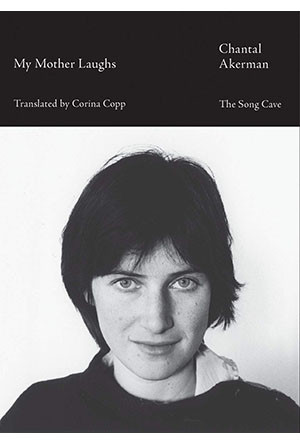

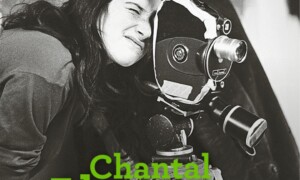

Born in Brussels in 1950 to Polish immigrants who survived the Holocaust, Chantal Akerman was exceptionally precocious, prolific, and prescient. Her films were inherently feminist, queer, and Jewish, but, more than anything, they resisted and refuted those (and all) labels by virtue of their raw humanism: they remain relevant and relatable to everyone who experiences them, confronted as we are by the absurdity, injustice, harshness, confusion, and profound beauty of the world. While her filmography is too often centred on the masterpiece she made at age 25, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles — which dramatically altered conventional perceptions of time and space in the cinema, and brought the previously neglected subjects of female subjectivity and domestic labour to the forefront — her energies, interests, and passions cannot be contained even within this immense work. Her over 40 short and feature films range from structuralist experiments to romantic comedies, musicals to literary adaptations, diaristic essays to biographical portraits to thinly veiled autobiographical road movies. She also created a large body of installation work and authored three books, the last of which — My Mother Laughs (recently translated into English), a searing memoir about her relationship with her mother — underscores Akerman’s innate restlessness, obsessive compulsions, fearless candour, and the porous boundaries between her art and her life.

Following her formative encounters with the films of Godard (she emulated the explosive finale of Pierrot le fou in her very first film, Saute ma ville, made when she was only 18) and, after a temporary move to New York, with the avant-garde work of Michael Snow, Jonas Mekas, and Andy Warhol, Akerman created her own unique brand of formalism, which could be read as a kind of hybrid of European high modernism and American experimentalism. Her signature long takes, oscillating between static, monumentalized compositions and sweeping tracking shots that set off movement against stasis (both literal and existential), probed the patterns and textures of everyday life, revealing what is imperceptible to most — not least of which was the potential for violence lurking within the quotidian. An acute and curious observer — of form, of architectural detail, of sound, of bodies in spaces — Akerman was also one of the first filmmakers to systematically acknowledge the fine line between documentary and fiction, imbuing her non-fiction works with lyricism and narrative suspense, and bringing to her narrative films a grasp of real-time rhythms and a sense of spatial and sensorial awareness that make us hyper-aware of our own presence in the world, prompting us to reset our own rhythms with those of her films.

With its insistently repeated motifs — epistolary exchanges, mother-daughter relationships, open-ended journeys, oral histories, performance, the sinister spectre of war — Akerman’s oeuvre is as thematically cohesive as her genres are varied, but it is also full of complexities, contradictions, and dualities. She was unafraid to combine the deeply personal with formal rigour, emotional intensity with Chaplinesque physical humour, the deadpan with the wonderfully melodramatic. Her work, as reflected through her own life, displays endless, complex dichotomies: romantic abandon and alienation; intimacy and distance; an indelible sense of place versus the disorienting displacement that made her a perpetual exile, shuttling between Brussels, New York, and Paris, never quite at home anywhere in the world; euphoria and melancholy; a furious productivity and constant need to work struggling against a paralyzing torpor. She excelled in the extremes: her films could be all narrative climax (such as her underrated, love-stricken Toute une nuit) or completely denarrativized, such as Les Rendez-vous d’Anna, which is structured from beginnings and endings and evinces a wrenching modern soul-sickness.

Akerman’s final film, No Home Movie — a visceral, diaristic account of the director’s final encounters with her mother, released the same year that Akerman herself ended her life, following a long battle with depression — evokes in its very title this double-edged quality inherent to her work: home as something both present and elusive, comforting yet claustrophobic, there but soon gone, physical but (mostly) mental. Akerman used to say that her mother, a woman who preferred to forget the trauma of her past, would often say there was nothing to say. And it is this “nothing” that comprises Akerman’s work — in other words, everything meaningful.